Colorado State University researchers have created a new, unique model to tackle a common and deadly problem western ranchers have struggled with for over a hundred years – cattle consuming toxic plants.

Cattle can eat too much larkspur, a common yet poisonous plant group, and die as a result. According to previous research, many cattle producers who graze their animals in dense larkspur pastures lose up to five percent of their herds annually. This equates to thousands of animal deaths. The U.S. Department of Agriculture values a cow’s worth at more than $1,000 each, which adds up to millions of dollars in lost income for ranchers every year.

A new study, recently published in the journal PLOS ONE, used agent-based modeling to find that management techniques may hold the key to safely grazing cattle in pastures with large concentrations of larkspur. Agent-based models simulate the actions of autonomous agents and their collective effects on a system.

“Agent-based models are a tremendous new tool for improving our understanding of livestock distribution and how our interventions can affect grazing outcomes,” said Kevin Jablonski, lead author and doctoral student in the Forest and Rangeland Stewardship department. “A major challenge has always been to understand how livestock behave on the landscape when we’re not there. Models can help with this.”

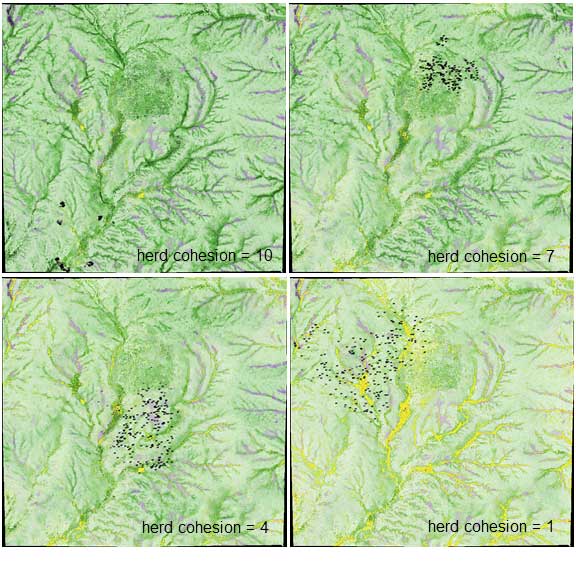

The CSU model, the first of its kind, found a 99.6 percent reduction in virtual cattle deaths when herd size (or stocking density) and cohesiveness both increased within realistic ranges. The long-held and widespread management practice has been to either avoid larkspur areas entirely or graze cattle outside the plant’s growing season. This study suggests a different approach.

A herd that stays together

In this new agent based model, Jablonski programmed his virtual agents, individual cows, with feeding and herding behavior inputs and set them loose on a realistic virtual landscape, using data from CSU Research Foundation’s Maxwell Ranch. The model included four different levels each of stocking density and herd cohesion totaling 480 simulations.

“All we did was program the cattle to do what they do individually and then said go,” Jablonski said. “We were surprised to see all these complex behaviors emerge that we knew existed.”

Behavior emerged as a key element in eliminating larkspur induced deaths. Jablonski explained that cattle variously exhibit leader and follower tendencies. If cattle stay in closely packed groups, individuals won’t wander off alone, say, to a forage patch rich with larkspur. It also appears that adding cows to a given area rich with larkspur could increasingly dilute the toxins a single animal would consume by spreading it throughout the group. Overall, each individual’s consumption would remain low enough that fatalities wouldn’t occur.

Co-author Randy Boone, professor in the Ecosystem Science and Sustainability department specializes in agent based modeling, and assisted with building the initial model.

“In most herding models, animals make relatively independent movements,” he said. “Kevin’s use of leaders and followers was unique and effective.”

Other landscape benefits

Paul Meiman, study co-author and associate professor in the Forest and Rangeland Stewardship department said these results provide ranchers with additional management options on their lands.

“Assume that a rancher is only using two thirds of the land area they have available to graze, as dictated by the presence of larkspur on the other third,” he said. “If they didn’t have to avoid larkspur, there is flexibility to manage livestock grazing across the ranch to best meet plant community and animal production objectives simultaneously.”

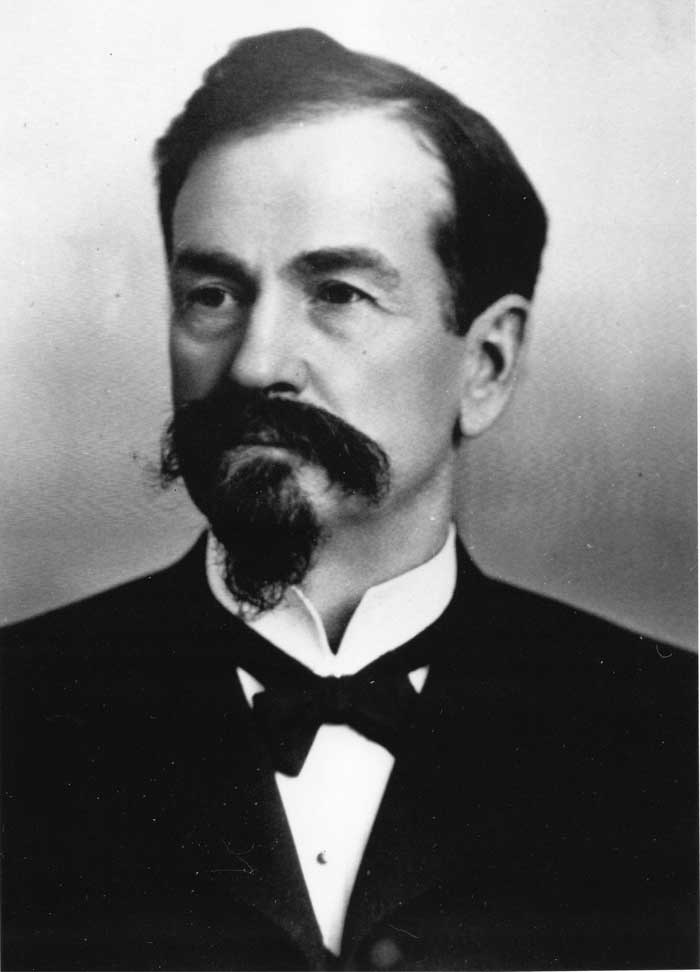

Interest in livestock management runs in Meiman’s blood. His great uncle, Frank C. Robertson, was a cattle rancher who drove thousands of head of cattle throughout western North America from the late 1800s to early 1900s.

His family’s journals recount a cattle drive when “Uncle Frank” repeatedly filled up his cattle on good pasture and then intentionally bedded them down together in poison weed, a term for larkspur. Meiman said this may have naturally taught the cows to avoid eating too much of the poisonous plant, and his great uncle didn’t lose any cattle. Robertson’s advice to other ranchers about this technique went unheeded, often with fatal consequences for those other herds.

“Maybe we’re finally picking up where Uncle Frank left off,” Meiman said.

A Paradigm Shift

The ideas generated by this new model point toward an emerging paradigm shift for livestock grazing management in the American west. A return to active livestock herding, like “Uncle Frank” practiced, promises both ecological and economic benefits. However, Jablonski said this may be a “difficult pill to swallow” for many ranchers already pressed for time and money.

That’s where models and other emerging technology can help. For example, affordable global positioning systems (GPS) tags can track cattle in real time and new virtual herding technology promises remote control of herd behavior, much like collars train dogs to stay within an invisible fence.

“Livestock distribution is the primary grazing management challenge. As we begin to use models, GPS, and virtual herding to alter how we learn about and influence distribution, there is potential to completely change how we manage grazing livestock within the next 10 years,” Jablonski said.