Caring for nature’s caretakers

CSU’s Center for Protected Area Management supports the people supporting conservation around the world

story by Jayme DeLoss

published April 10, 2024

In the race to find climate change solutions, one obvious strategy is to preserve what the environment is already doing by conserving natural areas. Just designating spaces for conservation isn’t enough, however. Those spaces need caretakers, and caretakers need training, resources and support.

For more than 30 years, Colorado State University’s Center for Protected Area Management has supported those caring for natural areas all over the world, including the Amazon – one of the most important ecosystems for stabilizing global climate.

Areas left undeveloped help to counteract climate change by cleaning air and water, reducing greenhouse gas through plant absorption of carbon dioxide, and storing carbon in soil and biomass. They also promote biodiversity and human health.

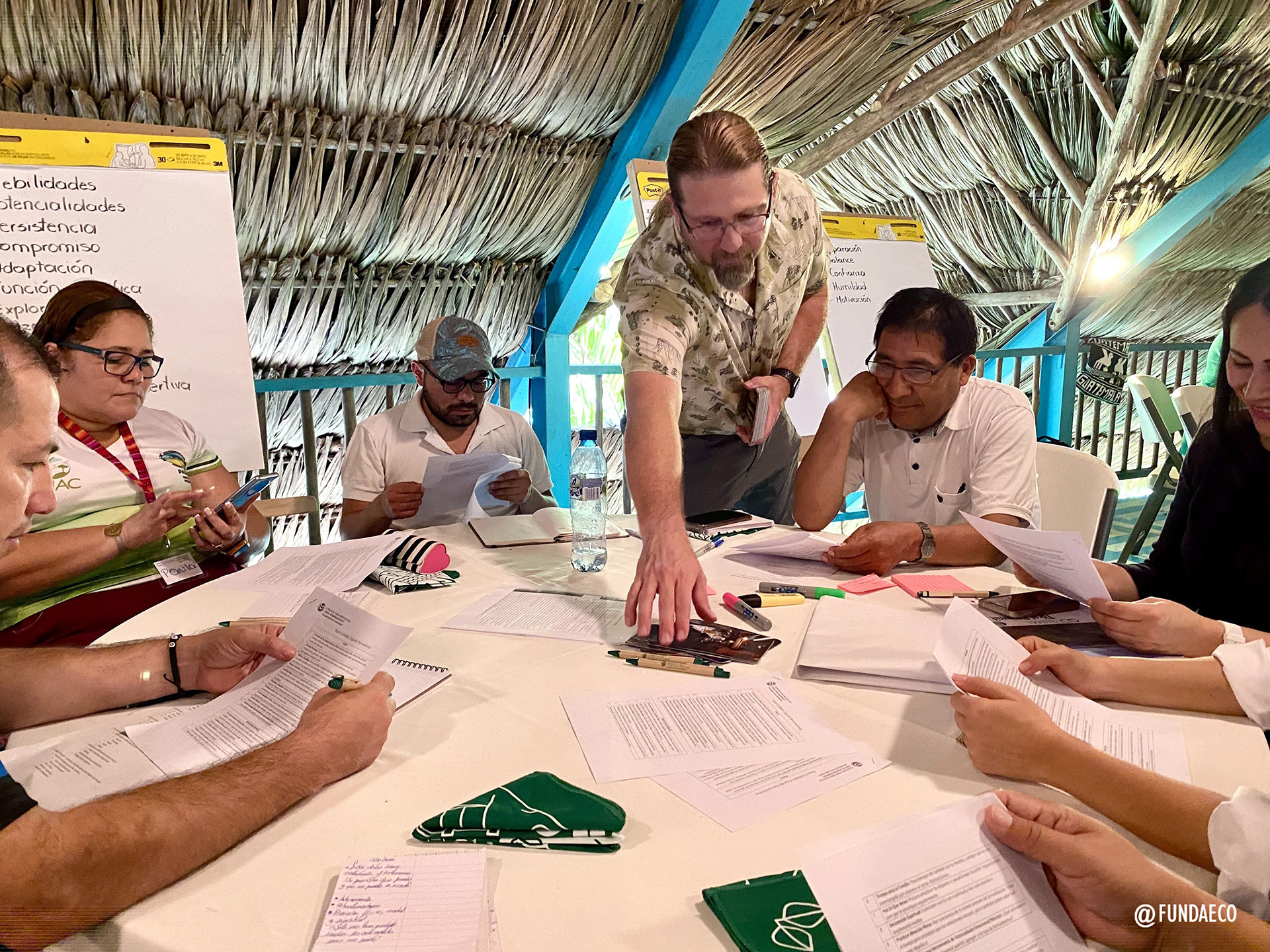

The Center for Protected Area Management aims to expand the capacity of governments, nonprofits and community members to care for natural areas and benefit from them. CPAM’s staff of about eight trainers and facilitators shares their conservation expertise with groups that ask for management assistance and builds communities of learning and practice to provide ongoing support.

People welcome

Conserving nature through protected areas doesn’t mean keeping people out, said Ryan Finchum, director of the center, which is housed in the Department of Human Dimensions of Natural Resources in the Warner College of Natural Resources.

“A big focus of ours is ensuring that these protected areas are people-friendly first,” he said. “They’re not protected from people; they’re protected for people.”

Finchum said that in the U.S., we take access to protected areas for granted because the national park system was founded with the dual mission of protection and visitation, while many other protected area systems in the world have restricted visitation to natural areas, admitting only scientists. However, excluding people – especially local people – from protected areas discourages support for long-term protection. If people aren’t allowed to benefit from natural areas, the land is more likely to be converted to other uses.

“People have to make a living, and if they can’t make a living with the forest standing, they’re going to make a living another way,” Finchum said. “We’ve got to find sustainable ways for people to have livelihoods that are compatible with protection.”

The center works with a wide range of protected areas, from government-established national parks to communal reserves and landscapes where people live and work. In collaboration with Brazil’s government and the U.S. Forest Service International Programs office, CPAM has trained hundreds of local guides in the Brazilian Amazon, creating economic incentive for conservation.

In addition to training guides, the center has helped Brazilian officials develop plans for public use and create visitor centers, trails and interpretive signs, while exchanging knowledge and best practices.

One close partner, Paulo Faria, head of protected area visitation and ecotourism with the Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation, the Brazilian administration that oversees federal protected areas, said that until the early 2000s, Brazil’s culture of managing protected areas had been focused entirely on preservation.

“We saw public use as a threat or enemy of nature conservation,” Faria said, but Brazil’s vision has evolved to view “contact with nature as essential for society to understand the importance of conserving protected areas and nature.”

Faria said CSU has influenced all 338 Brazilian federal protected areas through training and technical support over the past 12 years. He credits CPAM with training more than 700 conservation professionals, either directly or indirectly through leaders trained by CPAM.

Essential partnerships

Finchum said one of CPAM’s most important roles is connecting protected area managers within regions and across the world, so they can exchange ideas, share successes and support each other. The communities of learning and practice that CPAM facilitates help to ease the burnout, isolation and despair that managers sometimes feel. One such community has been active for 30 years since its formation during a CPAM event.

“Ultimately, we’re about creating a shared sense of hope for the future with the people who are entrusted with caring for these natural spaces around the planet,” Finchum said.

Conservation success hinges on coalitions of partners dedicated to protecting natural landscapes and seascapes, he added, so building those coalitions is a priority for CPAM.

“These areas aren’t going to sustain the values and objectives for which they were created in a vacuum,” Finchum said. “There are too many pressures on them.”

CPAM works closely with the U.S. Forest Service International Programs office and receives funding from the U.S. Agency for International Development. The Brazilian government also contributed substantially to CSU’s work in the Amazon.

“The U.S. Forest Service International Programs office has had an excellent partnership with CSU’s Center for Protected Area Management for over 20 years, enabling us to advance our community-driven conservation mission around the world,” said Val Mezainis, director of USFS International Programs.

Leaders needed

CPAM’s integration within CSU, a Carnegie R1 research university, has assisted its outreach mission to develop conservation leaders. The center works collaboratively with faculty scientists and graduate students and incorporates their findings into its work.

Associate Professor Jennifer Solomon’s research on barriers and supports for women in conservation led to a CPAM program that USFS International Programs cites as an example of the agency’s successful partnership with CSU.

“The innovative Women’s Leadership in Conservation program, run by CPAM, is rapidly creating an impactful cohort of global conservation leaders,” Mezainis said.

Lack of managers is a serious challenge facing conservation, Finchum said, one that will be exacerbated if the world succeeds in an ambitious 30×30 global goal, adopted by more than 190 countries, to protect 30% of Earth’s land, oceans and fresh waters by 2030.

“We don’t have enough people dedicated or hired to manage the protected areas we already have created,” Finchum said. “We need to ensure that the current lands that we have dedicated to protected areas are truly protected for people for the long term. This also means increasing global recognition and support for local and Indigenous community-run areas and ensuring their rights to remain on their lands. We’ve got to learn from past mistakes and make sure that creation of new protected areas is done in a more holistic, inclusive way.”