By guest columnist Kevin Crooks, director of the CSU Center for Human-Carnivore Coexistence at Warner College of Natural Resources

Like millions of other people, I watched with amazement the viral video last week of the intense interaction between a mountain lion and a hiker on a trail in Utah. Many media outlets have described this interaction as the mountain lion “stalking” the hiker, ready to “attack.” While no one can know the exact mindset or motivation of the animal, the context of the interaction, and the lion’s behavior, provide some clues. Watching it, I saw clues I learned from working with another carnivore, cheetahs.

Learning from cheetahs

Fresh from graduating with a Bachelor’s degree in Zoology from Colorado State University in 1989, I was fortunate to land a job with the San Diego Zoo’s Center for Reproduction of Endangered Species (now the Institute for Conservation Research). There, I worked at the cheetah breeding and research facility at the Wild Animal Park (now the Safari Park) in the foothills east of San Diego. I was one of three keepers at the facility whose daily routine was to enter the large, outdoor pens to feed the animals, clean the area and move cheetahs between pens when necessary. Occasionally, when we did, some cheetahs were less than thrilled, reacting to us with the type of “bluff charges” I saw from the mountain lion in the viral video. Ears pinned back, snarling, hissing, lunging forward and stamping front paws. To protect ourselves, we carried wooden poles that we would hit on the ground in front of us when necessary (never touching the cats). We would face the cheetahs, move slowly, and talk to them in a loud and firm voice. Despite these encounters, I understood that the cheetahs likely felt threatened, guarding their territories against intrusion by us humans, not intent on attacking me. Nevertheless, such interactions were memorable enough that I still remember them vividly, 30 years later, which brings me back to the viral video.

Maternal instinct

The interaction started when the hiker saw what he thought were bobcat kittens. He began recording them with his phone, when an adult mountain lion, presumably the mother, appeared and approached. An intense 6-minute interaction ensued, with the hiker slowly retreating, and the animal continuing to push him back down the trail. Occasionally, and dramatically, it bluff charged (reminding me of the cheetahs). It never attacked, and eventually, ran back towards the cubs. Mountain lions are considered “ambush” predators, meaning that typically they sit and wait for prey to pass, and then pounce, quickly, and with force. This mountain lion did nothing of the sort. Taken together, these clues suggest that the mountain lion was not stalking the hiker, but rather trying to protect her cubs and “escort” the hiker away from the area.

Sharing the trail

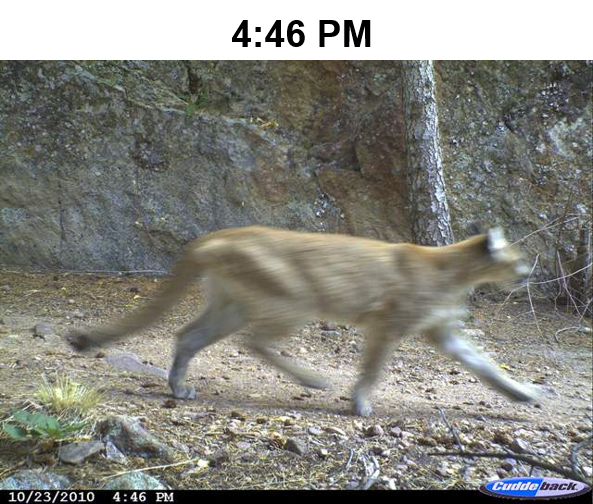

Of course, mountain lions can attack people, as was evident when a trail runner was attacked by a juvenile mountain lion west of Fort Collins last year. Such encounters are extremely rare. Mountain lions tend to be elusive and secretive, seldomly seen by people. Humans and mountain lions tend to coexist peacefully, even near places heavily populated by people. For example, our research team has deployed remotely-triggered wildlife cameras on recreational trails in the foothills of Fort Collins and Boulder—at times right along the urban edge. These cameras have recorded hundreds of thousands of photos of hikers, joggers and bikers recreating in these areas, and also hundreds of photos of mountain lions sharing these same trails with no resulting conflict. I expect few people even realized that mountain lions were in the vicinity. In all, mountain lions do an impressive of job of avoiding humans, despite being continually exposed to them along the urban-wildland interface.

For instance, below are images captured by a wildlife camera along the urban-wildland interface near Boulder, Colo. Though mountain lions and people sharing the trails pass the camera within minutes of one another, the humans remain unaware of their near brush with the carnivores.

From these viral videos and images, it’s clear we need to be aware and exercise caution when recreating in mountain lion country, or any areas with wildlife such as large carnivores, moose and elk that might harm people, particularly when threatened. To reduce the likelihood of an encounter with mountain lions, Colorado Parks and Wildlife recommends making noise, going in groups and keeping children nearby. A sturdy walking stick, as we had for the cheetahs, is not a bad idea. If you come upon a mountain lion, stay calm, don’t approach it, stop or back away slowly, keep eye contact, speak firmly and appear as large as possible. Most mountain lions will run away, but if they don’t, yell loudly, throw objects, pick up children and, if necessary, fight back.

Human-carnivore coexistence

Colorado is famous for its abundant wildlands and wildlife, which includes large carnivores such as mountain lions, black bears and coyotes. At the Center for Human-Carnivore Coexistence at CSU, our mission is to develop approaches to minimize conflict and facilitate coexistence between people and predators. Whether cheetahs protecting their enclosure or mountain lions protecting their cubs, when humans and carnivores come face to face, our own actions can help reduce the risk of conflict. With some knowledge and awareness of carnivore behavior, and our own behavior, along with a healthy dose of respect for these animals, humans and large carnivores can continue to coexist in the state.

Kevin Crooks is a Professor of Fish, Wildlife, and Conservation Biology at Colorado State University. He is a wildlife biologist who focuses on carnivore ecology, and has conducted studies of mountain lions in urban landscapes in Colorado and southern California. He is Director of the Center for Human-Carnivore Coexistence focused on integrating science, education, and outreach to minimize conflict and facilitate coexistence between humans and carnivores.