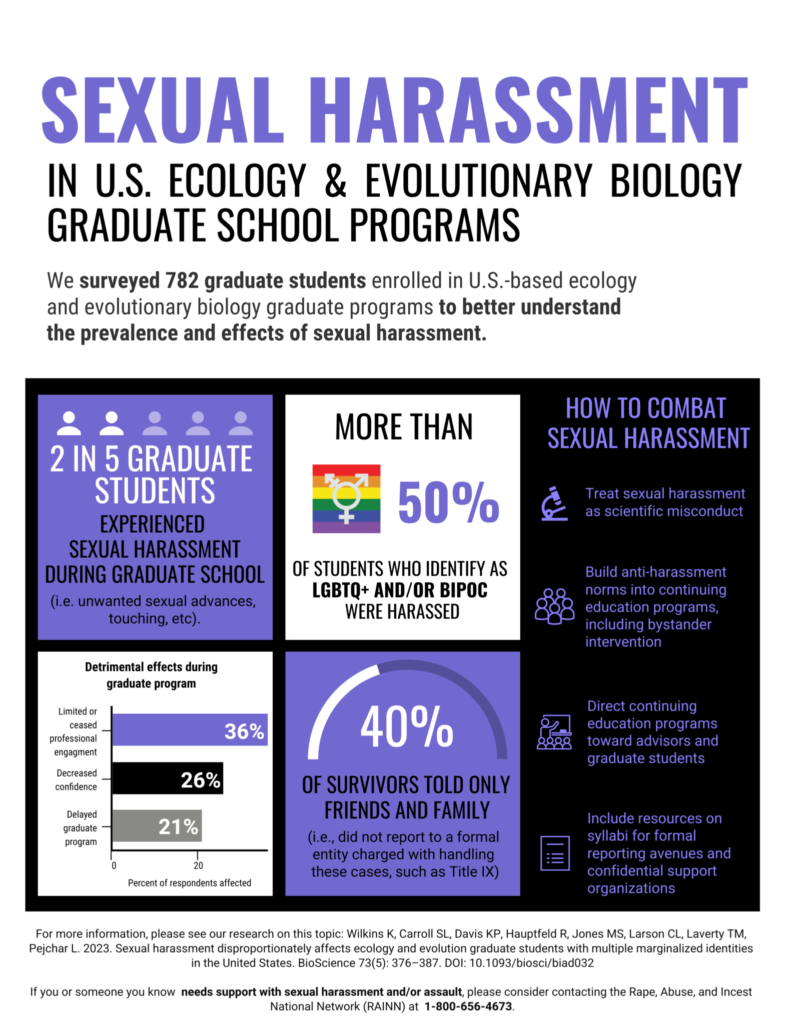

In a survey of 782 graduate students from 94 U.S. ecology and evolutionary biology programs, a Colorado State University research team found that nearly 40% had been sexually harassed during their graduate program. More than 80% of those students experienced harassment more than once, leading to profound impacts on their graduate school experience.

Although previous research has found that sexual harassment is prevalent in scientific fields, and more efforts have been made to understand sexual harassment following 2017’s #MeToo movement, less is known about the impacts of sexual harassment on graduate students at the intersection of gender, race/ethnicity, and sexual orientation.

“We were inspired to conduct this research because we kept hearing about students that had been harmed by sexual harassment in ecology and evolutionary biology graduate programs,” said Kate Wilkins, lead author of the paper that was started while she was a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Biology at CSU. Wilkins is now the Regional Conservation Director for Colorado in the Department of Field Conservation at the Denver Zoological Foundation.

The study, published in BioScience, included Wilkins’ former Ph.D. advisor, Liba Pejchar, a professor in the Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Conservation Biology in the Warner College of Natural Resources, and six other current or former CSU graduate students, encompassing three different WCNR departments.

Findings

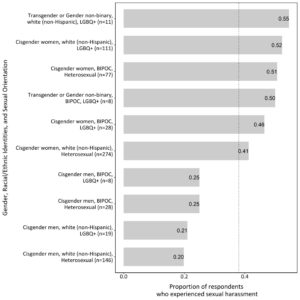

The study found that graduate students with two or more intersecting marginalized identities were disproportionately affected, causing survivors to be less successful by delaying completion of their graduate programs or changing careers altogether. More than 50% of the students who were sexually harassed identified as LGBTQ+ and/or BIPOC women.

More than one-third of respondents limited or ceased professional engagement activities, and more than 20% indicated that the harassment impacted their career trajectory, including no longer wanting to pursue a career in academia. The research found that these effects were magnified when the harasser was in a position of greater authority, such as a department head, professor, dean, or postdoctoral fellow.

#MeToo perceptions

The survey included a section about the #MeToo movement, which was founded by Tarana Burke in 2006 to help bring together sexual harassment survivors with similar experiences. The movement gained traction in 2017 as women began sharing their experiences on social media.

Almost all the respondents in the survey had heard of the #MeToo movement, with over three-fourths of respondents reporting that the movement helped increase their understanding of the prevalence of sexual harassment and what “counts” as sexual harassment, but less than one-fourth of respondents felt that the movement helped inform them how to navigate sexual harassment when it occurs.

While the overall perception was that the movement has helped increase a victim’s willingness to report incidents of sexual harassment/assault, respondents felt that witnesses and universities were less likely to report incidents and support sexual harassment victims.

Looking forward

Of the graduate students who did tell someone about being sexually harassed, 40% of survivors only told family and friends, and disclosures to official entities such as the Title IX Office and the Office of Equal Employment Opportunity were made at much lower rates, 15% and 3%, respectively.

The study also found that when sexual harassment was reported to formal entities, the rate of dissatisfaction with the outcomes among BIPOC survivors was much higher than among white (non-Hispanic) respondents. The respondents who reported feeling dissatisfied with the outcome felt that they weren’t taken seriously or were ignored, and that their institutions lacked transparent and consistent protocols for handling reports of sexual harassment.

Wilkins and the research team hope their findings will be used to make meaningful changes in how incidents of sexual harassment are handled at universities and in the sciences more broadly.

“We hope that this study helps shine a bright light on sexual harassment as a major barrier to advancing equity and inclusion in our discipline,” Pejchar said.

The paper identifies four ways in which universities can combat sexual harassment:

- Treat sexual harassment as scientific misconduct

- Build anti-harassment norms into continuing education programs including bystander intervention

- Include resources on syllabi for formal reporting avenues and confidential support organizations

- Direct continuing education programs toward advisors and graduate students

“We don’t want people taking just one class and thinking they are done with training,” Wilkins said. “We need to continue to educate ourselves and others so we can be vigilant allies to our peers, colleagues, and mentees, who continue to be harmed by sexual harassment.”

Resources for sexual harassment/assault survivors

Colorado State University offers resources to students and staff for reporting sexual harassment and assault, and support for survivors:

- Women and Gender Advocacy Center

- Office of Title IX Programs and Gender Equity

- Sexual harassment awareness training

- Sexual harassment complaint procedures

- Sexual assault information and resources

- Where to file a complaint

For anyone needing support with sexual harassment and/or assault, consider contacting the Rape, Abuse, and Incest National Network (RAINN) at 1-800-656-4673.

Authors of the study are Wilkins, Pejchar, Graduate Degree Program in Ecology Ph.D. candidates Sarah L. Carroll and Rina Hauptfeld in CSU’s Department of Ecosystem Science and Sustainability, Human Dimensions of Natural Resources Ph.D. graduate Megan S. Jones, Fish, Wildlife, and Conservation Biology Ph.D. graduates Kristin P. Davis and Theresa M. Laverty, and Wyoming Nature Conservancy conservation scientist Courtney L. Larson.