As the need for water for expanding urban areas and agriculture in arid regions grows, interbasin water transfers have become an increasingly common tool to satisfy demand, but their impact on the movement and gene flow of aquatic organisms is poorly understood.

A study out of Colorado State University in conjunction with the U.S. Geological Survey and U.S. Forest Service is one of the first to use genetics to understand how interbasin water transfers affect connectivity between previously isolated watersheds and how that connectivity can impact trout diversity.

The study called “Population genetics reveals bidirectional fish movement across the Continental Divide via an interbasin water transfer” and published in Conservation Genetics used genetic markers to determine if cutthroat trout utilize the Grand Ditch as a movement corridor across the Continental Divide. Grand Ditch, one of 44 interbasin water transfers in Colorado, diverts streams and creeks that flow into the Never Summer Mountains in northern Colorado over the Continental Divide at La Poudre Pass, delivering water to eastern plains farmers and Front Range cities.

“Natural watershed boundaries have historically served as biogeographic barriers, preventing movement and gene flow in fish,” said study co-author Yoichiro Kanno, a fish ecologist and associate professor in the Fish, Wildlife, and Conservation Biology department in the CSU Warner College of Natural Resources.

“While interbasin water transfers satisfy human need, their impacts on genetic diversity are likely to become a global issue,” said Kanno, who leads the Stream Fish Ecology and Conservation Lab at CSU.

Findings of the study show that the Grand Ditch is a conduit for fish movement bidirectionally both east and west ward, affecting the genetic structure of cutthroat trout populations. The results have implications for water management and ongoing trout conservation efforts, Kanno said.

Interbasin effects on biodiversity

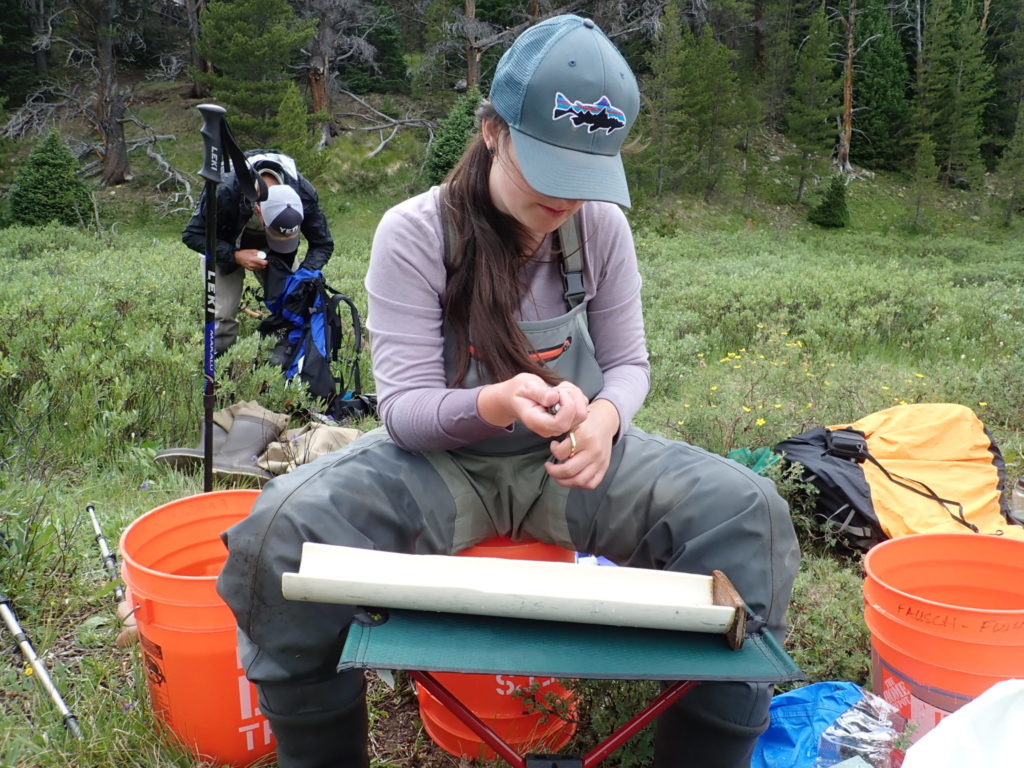

Researchers collected genetic data from 225 fish samples at five sites—two on the west side and three on the east side of the Continental Divide and examined genetic differences to determine whether movement was occurring.

“If the interbasin water transfer was not a corridor for movement, we’d expect to see the sites on the western side of the Continental Divide look very different from the sites on the eastern side, but that’s not what we saw,” said lead author Audrey Harris, who conducted research while earning her master’s degree in Fisheries, Wildlife, and Conservation Biology at CSU.

“Instead, we saw that fish from the Grand Ditch looked genetically similar to the fish on the eastern side of the Continental Divide, showing movement and hybridization.” This is an important finding because the six subspecies of Colorado cutthroat trout evolved due to physical isolation and a lack of gene flow, Harris said. This bidirectional movement also directly affects the success of the Poudre Headwaters Project, a collaborative project at the research site with the aim of reintroducing genetically pure greenback cutthroat trout to vast areas of the Cache la Poudre River.

“The Poudre Headwaters Project has spent time, money and effort to reintroduce greenback cutthroat trout to this area with the expectation that they will be isolated, and it’ll stay that way,” said Harris who now serves as a fisheries research geneticist at the Pacific States Marine Fisheries Commission.

“Grand Ditch could allow fish that are not greenback cutthroat trout to move into the project area and hybridize with these fish. It signals a big problem when the conservation goal is to maintain genetic integrity. Grand Ditch would also allow greenback cutthroat trout colonize streams on the western side of the Continental Divide, to which they are not native.”

The research team collaborated closely with Poudre Headwaters Project, and their findings will aid project managers in their ongoing efforts to conserve native trout populations. Specifically, managers plan to remove hybrid cutthroat trout from Grand Ditch and the tributaries it intercepts and have already constructed a barrier to prevent trout movement across the continental divide.

Balancing water demand and biodiversity conservation

Interbasin water transfers are an ever-growing solution to climate change-related water insecurity. In the U.S. alone, 2,161 interbasin transfers are in use, and worldwide 34 large-scale water transfer mega-projects exist—with an additional 76 megaprojects set to be completed by 2050.

Given the use of interbasin water transfers globally, the study results have implications for water and drought management worldwide, Kanno said.

“We are experiencing droughts in the West right now with Lake Powell and Lake Mead in Colorado at historically low levels,” Kanno said. “How do we negotiate this landscape of water shortage while maintaining the biodiversity of native species? This is a question we must answer.”

Dana Winkelman, study co-author and Unit Leader for the USGS Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit Program in Colorado, said the study begs bigger questions around interbasin water transfers’ ability to permanently change the evolutionary course of species.

“We’re trying to preserve the evolutionary history of these trout species,” Winkelman said. “If we allow these fish to come together, then we lose that unique history that developed over millions of years. Once we lose that, we lose it forever. We can’t get it back.”

Additional collaborators for the study included the National Park Service, Colorado Parks and Wildlife and Trout Unlimited.