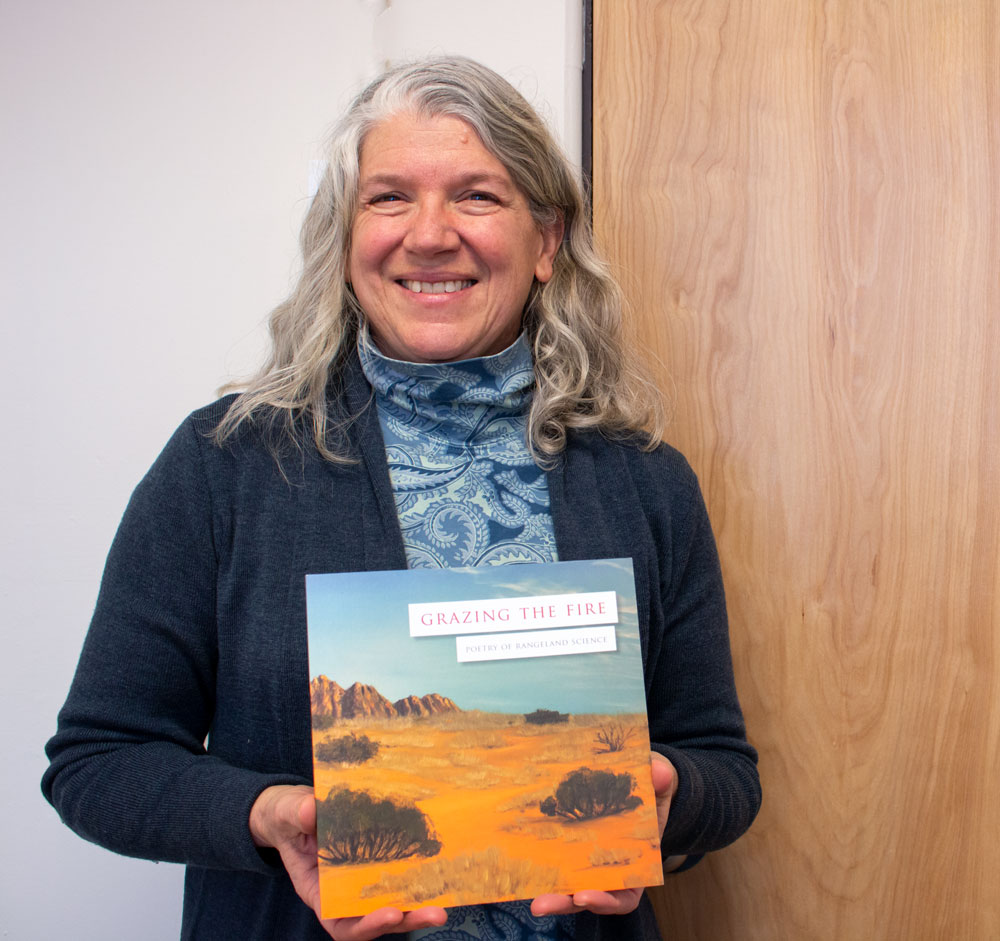

María Fernández-Giménez will be stepping down from her professor role at Colorado State University this spring. She has been at the forefront of collaborative community-based rangeland research her entire career, having worked extensively with land stewards in the western U.S. and Mongolia. She will continue as a Senior Research Scholar at CSU, focusing on community-engaged research that combines scholarship and creative writing.

What inspired you to pursue your career in rangelands?

I did my undergraduate degree in Philosophy, but always loved the outdoors and agriculture even though it wasn’t in my roots. My parents both had degrees; my Spanish father had a Ph.D. They both always encouraged me to learn and try new things, and supported my unconventional ideas.

I grew up in Illinois and went to college in the eastern U.S. To see the west, I went to work as a seasonal employee in the National Park Service. I also hitch-hiked across the west, backpacking through the Tetons, Glacier National Park, Olympic National Park and the Grand Canyon. As a seasonal at Bryce Canyon, I was exposed to controversies over livestock grazing on public lands, and I grew interested in the human history of the area. I conducted oral histories of ranchers in those small towns and developed a living history presentation for my evening campfire program. I’ve always been interested in people’s stories and their relationship to the land.

After my Park Service experiences, I wanted to understand the issue from ranchers’ perspectives, so I worked on a cattle ranch and later as a sheep herder to understand what that life and work was like. Those hands-on experiences gave me a deep respect for people who work on the land. But they didn’t provide me with the science I needed to draw my own conclusions about the public lands grazing controversies. So, I decided to go to graduate school in range management in order to gain a foundation in the science of rangeland ecology. Along the way, I found that I loved research—being able to ask any question and pursue the answers.

What set the stage for your career?

As I was finishing my Master’s in range management, Mongolia held its first democratic elections and entered a free-market economy after 70 years of socialism. There was very high voter turnout despite more than half the population living as nomadic pastoralists. Mongolia was an example of an ecosystem that had been sustainably grazed by livestock for millennia. It was undergoing huge changes economically and politically and I wanted to see how those changes would affect people’s livelihoods and land-use practices, and ultimately the ecosystem.

I started my research career in Mongolia and have been working there for over 30 years.

What are some of the highlights of your career?

I always wanted to work at CSU. It was my dream job. When I was hired in 2003, I immediately went back to northwest Colorado, where I worked as a ranch hand in 1987. Building on those early relationships with various government agencies, ranchers and CSU Extension, my students and I developed a series of research projects in the area over 15 years. The projects built on one another and all were community-based, involving local landowners, stakeholders and natural resource agencies in helping to define and carry out research to address their questions and create management tools to support sustainable rangeland stewardship.

Early on, I also wanted to reciprocate the generosity of the Mongolian herders I had lived and worked with, along with the scholars who helped me in Mongolia. To do this I brought a number of Mongolian graduate students to CSU, and hosted several Mongolian post-doctoral researchers and visiting scholars. These relationships and continuing work in Mongolia culminated in the Mongolian Rangelands and Resilience Project (or MOR2), an exceptional piece of science. We were an international, cross-cultural team, including many other CSU faculty, graduate students and post-docs. The project sought to understand how climate and socio-economic changes were affecting Mongolian rangelands and pastoralists and whether community-based rangeland management could help build system resilience. We studied the ecological, social and livelihood outcomes of community-based rangeland management in Mongolia across 36 counties in four different ecological zones. It was the most challenging and rewarding work I’ve done.

The most fun I’ve had doing research was during my last sabbatical in Spain a few years ago. I traveled around the entire Iberian peninsula and interviewed women working in extensive livestock production, visiting them on their farms and documenting their stories. I also had the opportunity to work with a young and dynamic group of women scientists who are also feminist, agro-ecological activists, which was inspiring. It showed me that we can do both excellent research and work for systemic change towards a more sustainable environment and just society for all. We’re continuing that work and will be holding a virtual public gathering and panel discussion with Spanish women pastoralists on May 19.

How has your expertise evolved over your career?

In hindsight, I realize I was always on the leading edge of new topics and approaches that have now become mainstream, like studies of traditional ecological knowledge or arts-based methods in research including poetic inquiry. Co-production and transdisciplinary research are all the rage now, but many of us have been using collaborative and participator research methods for decades. That’s just the way I’ve always originally done things. The process was always the product. It’s more about how we engage with each other in research, teaching, outreach and engagement.

Towards the end of my career, I have shifted my focus to diversity, equity and inclusion work in my role in the department, university, and the Society for Range Management society I belong to. My research also reflects this change, with a focus on engaging historically underrepresented or minoritized communities in our research—like women livestock producers and Indigenous and Hispanx/Latinx/Chicanx ranchers.

What have you appreciated about CSU during your career?

What drew me to CSU was the systems approach to ecosystems and human communities that CSU was known for, especially in rangelands. From the beginning, there was always this openness to research collaboration across departments and disciplines at CSU. The atmosphere really embraces the “beginner’s mind,” which is essential to true scientific creativity and progress. The culture of collaborative science initially helped me get my career off the ground and integrate the social science side of my expertise with other ecological fields.

I loved working with students. I mentored graduate students in collaborative ways of conducting science with communities, and I loved teaching hands-on undergraduate field classes in rangeland monitoring and assessment. I had high expectations of students and pushed them to think at a higher level. It was very rewarding to mentor international students who earned their PhDs at CSU and returned to Mongolia and Kenya to have an impact in their own communities.

The support I received from leaders at CSU helped me grow from a young collaborator into an effective leader in formal and informal leadership roles within the university and beyond. Our department has assembled a great group of faculty members and staff who are open minded and willing to learn from each other. Under the leadership of Linda Nagel, we’ve cultivated a culture of trust and continual learning, where everyone is committed to learning together to make our pedagogy more inclusive and support success of all our students.