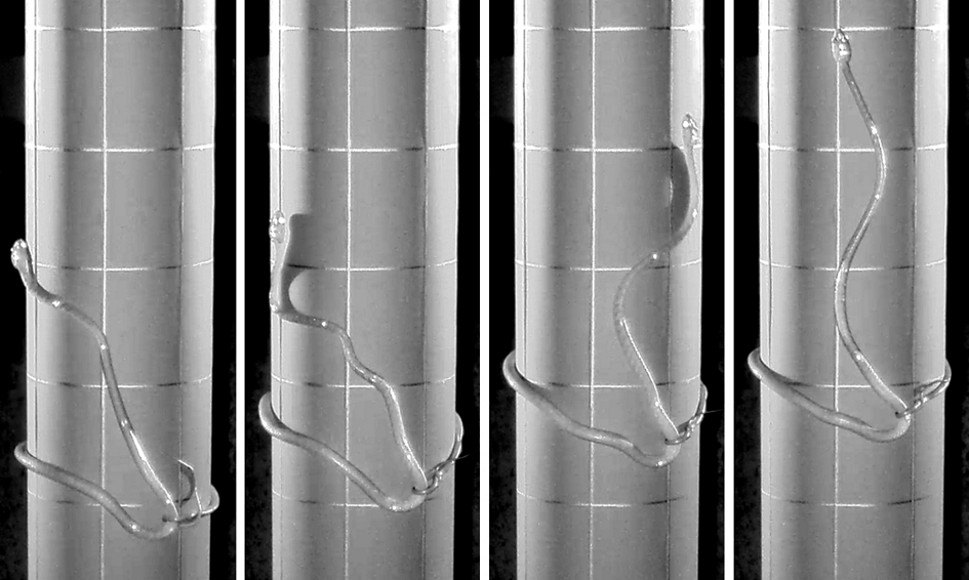

This lasso locomotion, in which the snake bends its body into a loop to grip vertical poles, may contribute to the success and impact of this highly invasive species. Photo: Tom Seibert/CSU

A team of researchers from Colorado State University and the University of Cincinnati have discovered a new mode of locomotion that allows the brown tree snake to climb much larger smooth cylinders than any previously known behavior.

This lasso locomotion, in which the snake bends its body into a loop to grip vertical poles, may contribute to the success and impact of this highly invasive species. It allows these animals to access potential prey that might otherwise be unobtainable and may also explain how this species could climb power poles, leading to electrical outages.

Researchers said they hope the findings will help people protect endangered birds from the snakes.

The study, “Lasso locomotion expands the climbing repertoire of snakes,” is published Jan. 11 in Current Biology.

‘Unexpected’ locomotion discovered on U.S. island territory of Guam

For nearly 100 years, all snake locomotion has been traditionally categorized into four modes: rectilinear, lateral undulation, sidewinding and concertina.

This discovery of a fifth mode of locomotion was the unexpected result of a project led by CSU Emeritus Professor Julie Savidge aimed at protecting the nests of Micronesia starlings, one of only two native forest species still remaining on Guam.

Savidge, part of the Department of Fish, Wildlife and Conservation Biology at CSU, said that the brown tree snake has decimated forest bird populations on the island, where the discovery took place. The snake, which is nocturnal, was accidentally introduced to the local ecosystem in the late 1940s or early 1950s. Shortly thereafter, bird populations started to decline.

The scientist conducted her doctoral dissertation research on Guam in the 1980s and identified the snake as the culprit.

“Most of the native forest birds are gone on Guam,” said Savidge. “There’s a relatively small population of Micronesian starlings and another cave-nesting bird, the swiftlet, that has survived in small numbers. The starling serves an important ecological function by dispersing fruit and seeds which can help maintain Guam’s forests.”

CSU’s Tom Seibert, co-author and emeritus faculty, said the team was attempting to use a three-foot long metal baffle to keep the brown tree snakes from climbing up to bird boxes. These same baffles have been used to keep other snakes and raccoons away from nest boxes in the yards of birdwatchers. But this new study suggests these might pose little obstacle to brown tree snakes.

“We didn’t expect that the brown tree snake would be able to find a way around the baffle,” he said. “Initially, the baffle did work, for the most part. We had watched about four hours of video and then all of a sudden, we saw this snake form what looked like a lasso around the cylinder and wiggle its body up.”

Seibert said that he and CSU biologist Martin Kastner almost fell out of their chairs when they first observed this new form of locomotion.

“We watched that part of the video about 15 times,” Seibert said. “It was a shocker. Nothing I’d ever seen compares to it.”

Brown tree snake is a ‘champion climber’

To confirm the discovery, the team subsequently reached out to University of Cincinnati’s Bruce Jayne, professor of biological sciences and an expert on different aspects of locomotion and muscle function, especially in snakes. Brown tree snakes, in particular, are champion climbers, said Jayne, study co-author.

“Brown tree snakes are especially good at getting almost anywhere,” Jayne said. “It’s impressive. They can climb vertically using even the tiniest projections on a surface, and they can bridge enormous gaps in the tree canopy. They can push themselves up vertically more than two-thirds of their body length.”

Jayne said snakes typically climb steep, smooth branches or pipes using a movement called concertina locomotion in which the snake bends sideways to grip at least two regions.

But with lasso locomotion, the snake loops its body around to form a single gripping region.

Seibert returned to Guam to record high-resolution video of this new climbing method so that Jayne could better interpret the snakes’ movements.

“It wasn’t obvious how they were able to climb a cylinder,” Jayne said. “The snake has these little bends within the loop of the lasso that allow it to advance upwards by shifting the location of each bend.”

Lasso locomotion is more physically demanding than other climbing methods, Jayne said.

“Even though they can climb using this mode, it is pushing them to the limits. The snakes pause for prolonged periods to rest,” he said.

Savidge, a self-described ecologist who has worked with brown tree snakes for more than three decades, said the discovery of a new mode of snake locomotion is “quite exciting.”

“Hopefully what we found will help to restore starlings and other endangered birds, since we can now potentially design baffles that the snakes can’t defeat,” she said. “It’s still a pretty complex problem.”

Jayne said what the team discovered shows how amazing brown tree snakes are.

“I’ve been working on snake locomotion for 40 years and here, we’ve found a completely new way of moving,” he said. “Odds are, there is more out there to discover.”

Michael Miller, public information officer at the University of Cincinnati, contributed to this article.