Seismology records growing rumble of climate change

story by Jayme DeLoss published Nov. 6, 2023Since the late 1980s, modern digital seismic stations around the world have been taking the planet’s pulse. The low, steady thrum of ocean waves – once considered background noise by seismologists – has been intensifying since the late 20th century, according to a study led by Colorado State University.

The study, published in Nature Communications, examines data from 52 seismic stations recording the motions of the Earth once per second for more than 35 years. This decades-long record supports independent climate and ocean research that suggests that storms are intensifying as the climate warms.

“Seismology can provide stable and quantitative measures of what’s going on with the world’s ocean waves and complements studies using satellite, oceanographic and other methods,” said lead author Rick Aster, a CSU geophysics professor and head of the Department of Geosciences. “The seismic signal is both consistent with these other studies and shows the sorts of features that we may expect from anthropogenic climate change.”

Aster and his co-authors with the U.S. Geological Survey and Harvard University studied the primary microseism – a seismic signal created by large, long-period waves as they roll across shallower areas of the global ocean. The seafloor in coastal regions experiences the constant push and pull of these waves, and these pressure variations generate seismic waves that are picked up by seismographs.

Seismographs are best known for monitoring and studying earthquakes, but they also detect many other things, including glacial movements, landslides, volcanic eruptions, large incoming meteors and noise from cities. Seismic waves from diverse forces on the surface or inside the Earth can be identified at great distances, even in some cases on the opposite side of the world.

“As the atmosphere and ocean become warmer, they contain more energy, so storms become more intense, and storm-driven ocean waves increase in size and energy,” Aster said. “Increasingly energetic ocean waves directly increase the intensity of seismic waves.”

Making (bigger) waves

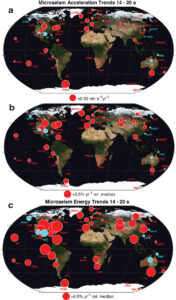

Seismic signals showed that waves in the notoriously stormy Southern Ocean around Antarctica were, predictably, the most intense on the planet, but North Atlantic waves have intensified the most rapidly in recent decades, reflecting intensifying storms between eastern North America and western Europe.

Multi-year climate patterns like El Niño and La Niña, which influence the strength and distribution of global storms, also can be observed in the data, in addition to a steady climb in wave energy that mirrors the widespread increase in global ocean and air temperatures and larger storms.

“It’s clear that we’re seeing the general signal of storm activity around the world in these long-term seismic records in addition to a long-term intensification, attributed to global warming,” Aster said. “It seems like a small signal from year to year, but it’s progressive and becomes very clear when you’ve got 30-plus years of data to work with.”

Aster and his colleagues found that globally averaged ocean wave energy has increased at a median rate of 0.27% per year since the late 20th century and 0.35% per year since January 2000.

Stormy forecast

Aster said bigger waves and bigger storm-related surges, combined with rising sea level, are a serious, global issue for coastal ecosystems, cities and infrastructure.

“We’re going to have to implement resilient strategies, as well as to try to mitigate climate change itself, to ensure that our coastal populations and ecosystems are going to be protected from an increasingly stormy future,” Aster said.

Professor Rick Aster further explains this research in an article written for The Conversation: “How global warming shakes the Earth: Seismic data show ocean waves gaining strength as the planet warms.”