A team from Colorado State University has discovered unique insights about the role of silviculture in high-elevation forests on the brink of climate change.

Silviculture is the practice of intentionally managing the growth of forests to meet certain objectives. With expectations for a hotter and drier future climate, one goal of silvicultural treatments in the southern Rocky Mountains has been to manually create conditions necessary for new generations of trees to survive and thrive.

In the new study, recently published in the Canadian Journal of Forest Research, CSU researchers detail some surprising contrasts in the relative influence of Engelmann spruce regeneration factors within managed forest stands.

“Managing these forests means understanding the natural and designed environments needed for a seed to develop into a young tree that can stand on its own,” said lead author Edward Hill, a master’s student in the department of Forest and Rangeland Stewardship.

The results indicated that moisture availability was less of a factor for regeneration, while a longer growing season and open growing environments created by forest treatments had greater positive influences on juvenile tree survival in treated stands.

Creating the environment

Engelmann spruce forests typically rely on a narrow range of temperature and moisture conditions to grow.

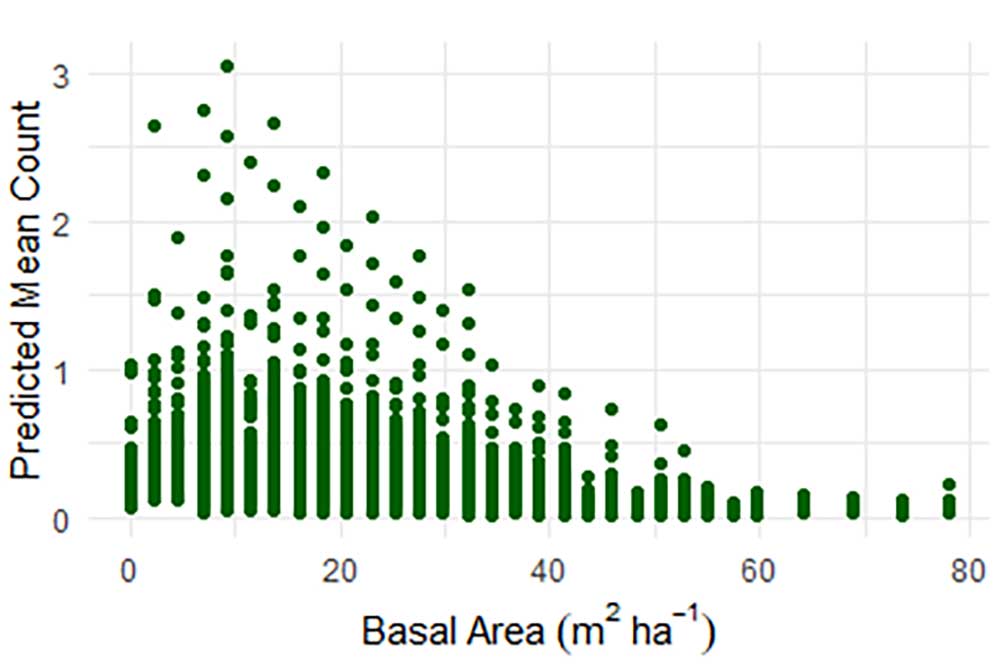

The researchers obtained measurements of 15 variables, including annual averages for precipitation, temperature and solar radiation, heat-moisture indices, frost-free periods and humidity. Using a model, the team combined the variables with factors such as basal area, which shows the relative density of trees in a stand. This measurement is a good indicator of the degree to which overstory, or tree canopy, effects the forest floor.

As part of the study, Hill combined tree data with 20 years of climate data to derive over 9,500 observations of annual tree establishment in the model.

The researchers found that open environments created by forest treatments were comparable to the effect longer growing seasons had on juvenile trees. Seedling response to these effects were strong and positive as the first five years of establishment progressed, while the influence of moisture availability was less, even for this highly moisture-dependent species.

“There is a tension between growing season effects and moisture availability,” co-author and CSU Assistant Professor Seth Ex explained. “Spruce respond well to warmer conditions, but these conditions usually result in less available moisture for growth. There’s a sweet spot in there somewhere.”

By controlling overstory density, silvicultural harvesting treatments can insulate juvenile trees from different environmental stresses by allowing a beneficial amount of precipitation and sunlight to reach the forest floor for retention and growth.

Establishment over time

The study findings reflected the first five years of juvenile tree establishment for trees that originated each year between the treatment periods of 1987-1995 and 2010. Surprisingly, the team found a strong increase in annual tree establishment over time, which held true even through a severe four-year drought that hit the Southwest in the early 2000s.

“The question we are exploring is to what extent do the impacts of our management actions and climate interact to affect regeneration in the long run?” said Hill. “We did not expect to see no disruptions to the establishment of new trees during the drought period.”

This study adds new insight to the limited amount of research available from managed subalpine forests in the southern Rockies over longer periods of time.

Researchers said questions remain about how climate change will affect these high elevation areas in the future, but using existing information in new ways may shed more light on silviculture’s role in forest management.

The research team used a data set that was originally created by CSU alumnus and co-author Curtis Prolic for his master’s thesis. Prolic is now a forestry technician for the Ashley National Forest in Vernal, Utah.