Adapted from a Massachusetts Institute of Technology news release.

If we could rewind the tape of species evolution around the world and play it forward over hundreds of millions of years to the present day, we would see biodiversity clustering around regions of tectonic turmoil. Tectonically active regions such as the Himalayan and Andean mountains are especially rich in flora and fauna due to their shifting landscapes, which act to divide and diversify species over time.

But biodiversity can also flourish in some geologically quieter regions, where tectonics hasn’t shaken up the land for millennia. The Appalachian Mountains are a prime example: The range has not seen much tectonic activity in hundreds of millions of years, and yet the region is a notable hotspot of freshwater biodiversity.

Now, an MIT-led study involving CSU geoscientist Sean Gallen has identified a geological process that may shape the diversity of species in tectonically inactive regions. In a paper published in Science, the researchers report that river erosion can be a driver of biodiversity in these older, quieter environments.

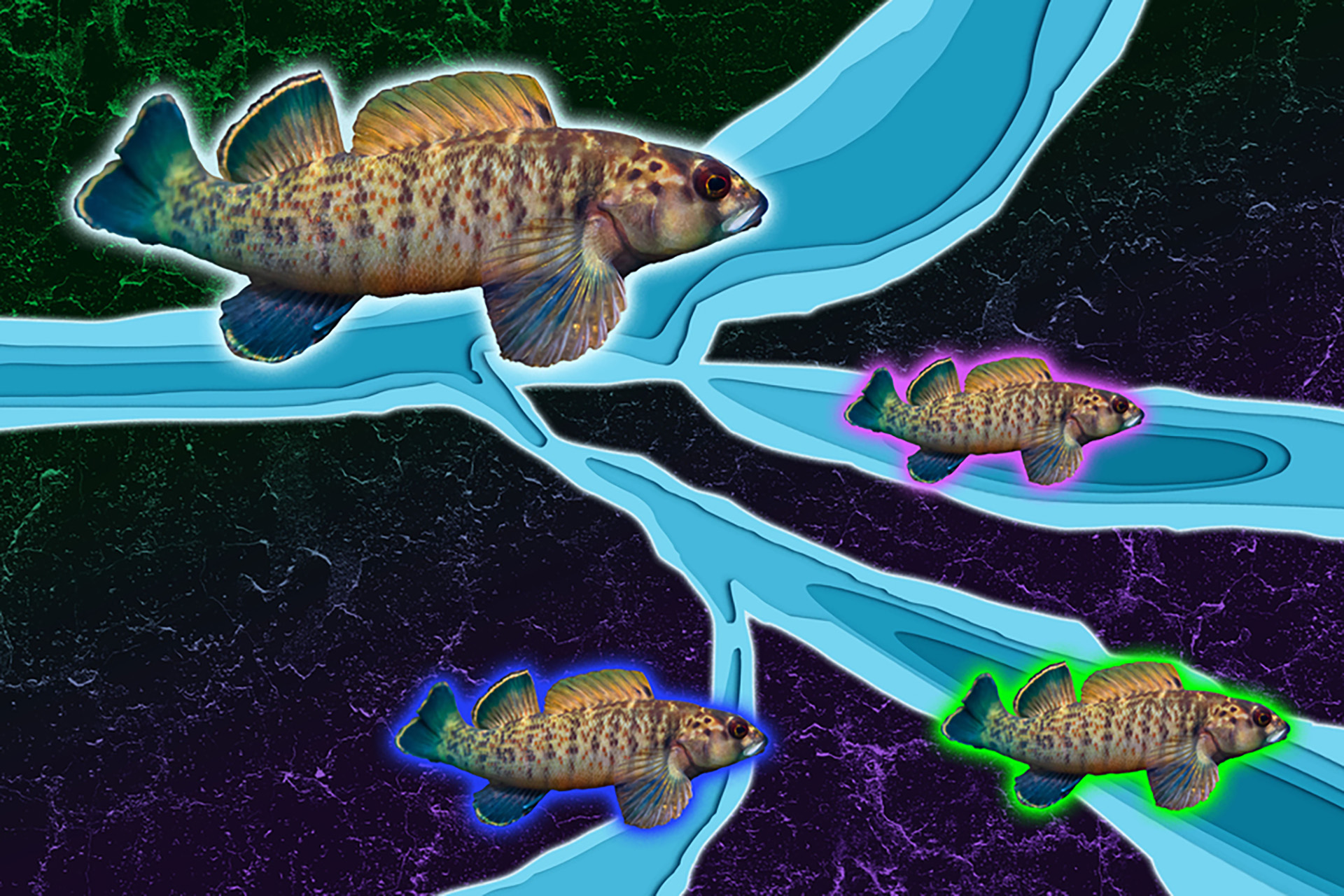

They make their case in the southern Appalachians, and specifically the Tennessee River Basin, a region known for its huge diversity of freshwater fish. The team found that as rivers eroded through different rock types in the region, the changing landscape pushed a species of fish known as the greenfin darter into different tributaries of the river network. Over time, these separated populations developed into their own distinct lineages.

The team speculates that erosion of specific rock types likely drove the greenfin darter to diversify. Although the separated populations appear outwardly similar, with the greenfin darter’s characteristic green-tinged fins, they differ substantially in their genetic makeup. For now, the separated populations are classified as one single species.

“Give this process of erosion more time, and I think these separate lineages will become different species,” said lead author Maya Stokes, who carried out part of the work as a graduate student in MIT’s Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences.

The greenfin darter may not be the only species to diversify as a consequence of river erosion. The researchers suspect that erosion may have driven many other species to diversify throughout the basin, and possibly other tectonically inactive regions around the world.

“The most exciting aspect of this study is that the combined legacy of plate tectonics, which sets the distribution of different rock types, and how the landscape evolves as it erodes those rocks is imprinted in the distribution and DNA of fishes in the study region,” said Gallen, who is an assistant professor of geosciences in the Warner College of Natural Resources. “It is an exceptional example of how all aspects of the Earth system are tightly linked and interconnected.”

The study’s co-authors include collaborators at Yale University, the University of Tennessee, the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, and the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA). Stokes is currently an assistant professor at Florida State University.

“This is certainly the most interdisciplinary and creative work I’ve had the pleasure of participating in,” Gallen said.